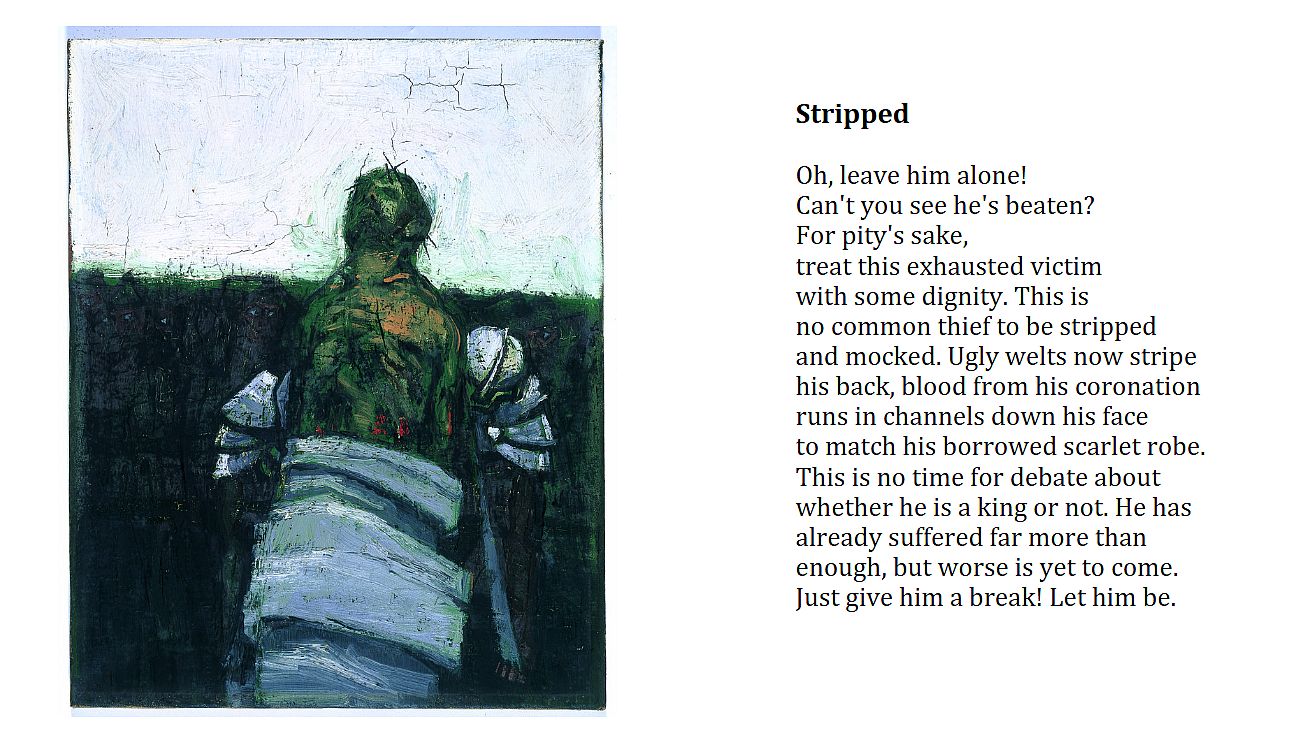

The Stripping of Our Lord by Philip Le Bas

Matthew 2727-31

Anger can, and often is, destructive; but it can also be a positive force, strengthening us to take action against all forms of injustice and cruelty, from the playground bully to the horror of war. All four gospels relate the story of Jesus displaying a right royal show of anger when faced with the materialistic desecration of the Temple (Matthew 2112-13; Mark 1115-17; Luke 1945-46; John 213-17). We excuse Jesus’s surprisingly violent behaviour on this occasion by calling it righteous anger; and similarly, when we are faced with the torture and mockery of a broken man, responding with anger towards the perpetrators feels like quite a healthy reaction.

Jesus looks far from angry in this image by Le Bas: he is physically and emotionally exhausted, the colours are dark and muted rather than violent and the figure is tightly constrained. It is for us, rather than Jesus, to be angry as we witness this. Too much anger, especially if it doesn’t find safe expression, is likely to be destructive, though expressing it in safe ways can, on occasion, be cathartic. It is entirely understandable that we should be sad as we reflect on the Passion story, but there are also aspects of the story that it is reasonable for us to be angry about, as long as that doesn’t lead to fruitless aggression.

The victim in this representation, does not even raise an arm to defend himself. He is beaten, defenceless and doomed to a painful death. Perhaps it is reasonable for us to react with some degree of anger here, as should surely also be our response when we discover other defenceless people suffering from injustice in the world today.