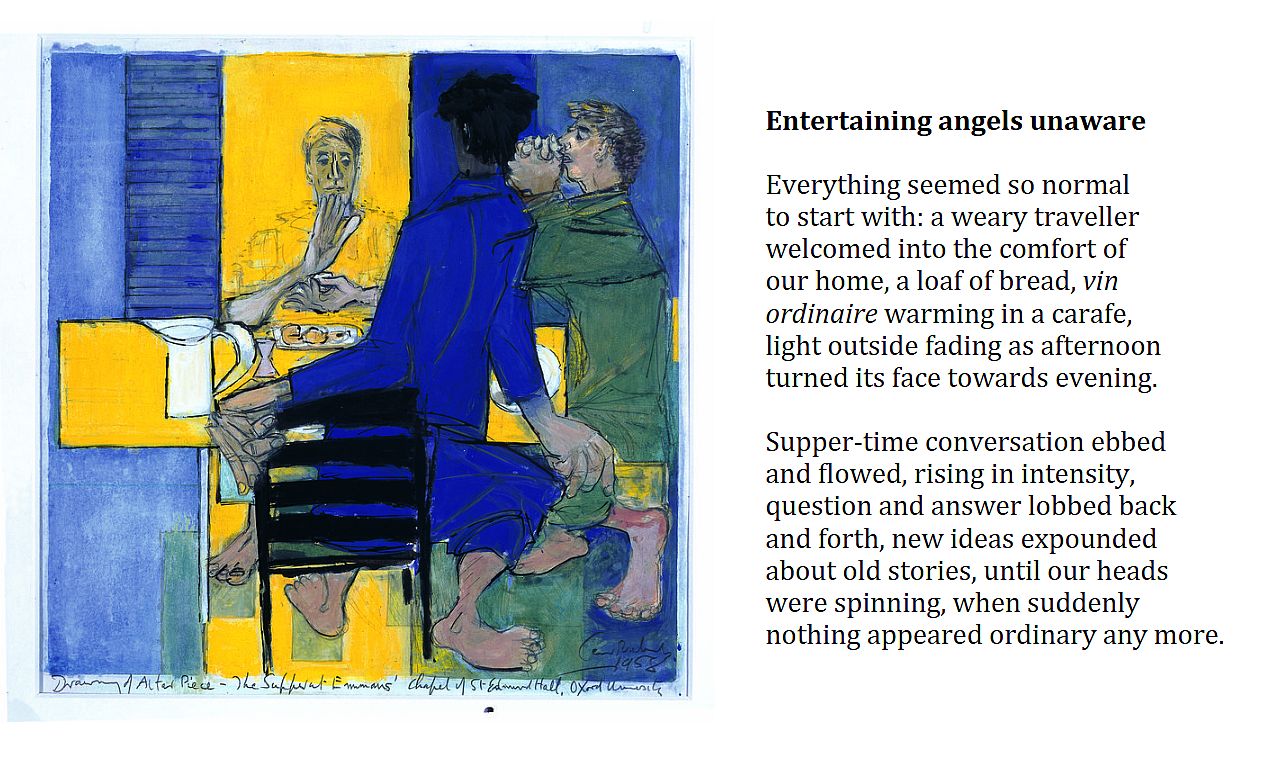

The Supper at Emmaus by Ceri Richards

The Supper at Emmaus by Roy de Maistre

Although so different in style, the similarities between these two works are striking. The subject matter, of course, demands that there be three, and only three, characters in the picture and in both cases the figure of Christ is, unsurprisingly, at the centre of the painting looking out towards us.

The Gospel story tells of two of Jesus’ disciples walking the seven miles from Jerusalem to their home in Emmaus, sharing their grief and bafflement as they trudge along. Then a stranger joins them and, having enquired about their distress, expounds the Scriptures to them in a way that helps them to understand the significance of the crucifixion and apparent resurrection of Jesus. On reaching their destination, the two disciples invite Jesus in to continue talking while they share a meal. Then, as Jesus lifts the bread set out for the meal and, as was the custom, blesses it, their eyes are opened with shock and joy to the true identity of their guest. At that point, Jesus disappears, leaving them to return at speed to Jerusalem to join the other disciples in spreading the amazing news that the man they had all seen suffer a painful death was alive.

Richards uses simple, predominantly primary colours to convey the moment of revelation, and his Emmaus couple are almost comedic as they bend towards each other and gaze in astonishment at Jesus. The table itself, at which Jesus raises his hand in blessing, has more than a hint of an altar.

The de Maistre oil painting, with its muted, but rich colours, is a deeply sensitive treatment of the event that encapsulates one of the most human yet divine stories in the Gospel. The moment at which the disciple on the right of the picture lunges forward with excitement on recognising Jesus offers a possible variation on the Noli me tangere images celebrating the moment at which Mary Magdalene, at the resurrection, recognised her dear friend and lord but was prevented by Jesus from embracing him. Rather than preventing the Emmaus disciple from catching hold of him, Jesus simply disappears from sight.

Both paintings base the form of their work on the shape of the Cross, which is not negated, but redeemed by the Resurrection. In neither painting is one of the disciples unambiguously a woman, though it has always seemed to me that two people, returning to their home and inviting a new friend in to supper, were most likely to be a married couple.

A short verse towards the end John’s gospel has always fascinated me:

Meanwhile, standing near the cross of Jesus were his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary, the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. (chapter 2025).

Mary was clearly a common name in 1st century Palestine, but it is unlikely that Mary the mother of Jesus should have a sister also called Mary. It would, however, be unremarkable if she had a sister-in-law with that name. There is often some confusion over names, and especially their spellings, in the texts that have come down to us, so it is not impossible that the Clopas who stood with others at the foot of the cross at the crucifixion, and who was the husband of Mary, Jesus’s aunt, was the same as the Cleopas who, the next day, wended his sad and weary way homewards to Emmaus. If this conjecture is not totally far-fetched, then maybe we have the name of the second disciple who lived in Emmaus and was married to Cleopas: Mary.

As ever, the bible stories raise tantalising questions and leave uncertainties shivering in the wind!