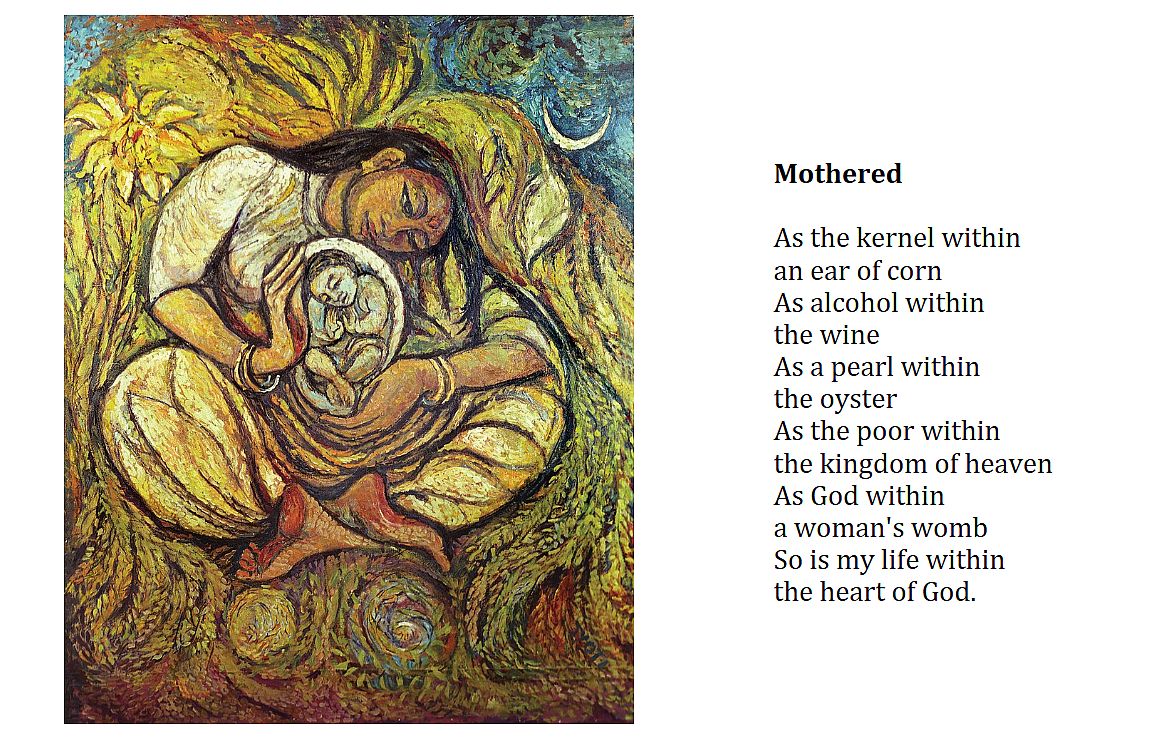

This is one of the most striking works of art in the collection, both for the beauty of its form and colour and for the spiritual interpretation that allows the viewer to respond to God our Mother in confidence and love. As with all the best symbols, it can be interpreted in different ways. It can celebrate Mary bearing the divine child, or the presence of God in all Creation and in the inner sanctum of our hearts, but most of all, for me, it is a reminder that my life, the people I love, the beauty of Nature, the challenges of the world and, yes, our pain, lack of faith and lostness, are all held securely in the love of God.

The twentieth century gradually made room for a more feminine understanding of God and many individual Christians and a fair number of churches now feel entirely comfortable praying to God our Mother. However, this aspect of God is much more ancient and established than modern theological enquiry might suggest. There are biblical precedents such as Isaiah 6613: As a mother comforts her child, so I will comfort you; and Jesus himself, faced with the unworthiness of Jerusalem and his love for that undeserving city, declared: How often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings. (Matthew 2327).

St Anselm, writing in the 12th century, described Jesus Christ as our great mother:

And you, Jesus, are you not also a mother?

Are you not the mother who, like a hen,

gathers her chickens under her wings?

Truly, Lord, you are a mother;

for both they who are in labour

and they who are brought forth

are accepted by you.

(from Prayers and Meditations of St Anselm, trans. Benedicta Ward (London, 1973))

It is also well-known that the 14th century mystic, Julian of Norwich, frequently celebrated the motherhood of God, of whom she declared: God is our mother as truly as he is our father. She even went so far as to describe the person of Christ as Jesus Our Mother who feeds and nourishes us from his own body.

Perhaps this glance back at history goes some way towards accounting for the emotional impact of Sahi’s painting that focuses so clearly on a feminine, maternal image, sharpening the impact and drawing us into a deeper understanding of God.

Apparently the image is based on an Indian grinding stone, used to prepare flour for bread-making – which in itself brings to mind the daily prayer: Give us this day our daily bread. The circular form of the mother contains the vulnerable child at its centre and one can almost feel her life blood flowing into the baby, giving life and strength. The impact of the painting is accentuated by the harmonious form and colours, leaving the viewer with a feeling of peace.

The earth colours bear some resemblance to the palette Stanley Spencer used in his deeply spiritual series of paintings, ‘Christ in the Wilderness’. One of those, The Hen, draws on the image of a mother hen with her chicks and clearly refers to the passage in Matthew that we have already noted: How often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings.

Spencer’s dramatic and moving rendering of The Scorpion is my favourite of the Christ in the Wilderness series. In it Spencer uses a circular, enfolding shape for the figure of Christ, similar to Sahi’s treatment of the Madonna. This draws the eye in and focusses attention on the centre, where Jesus is contemplating a scorpion held gently in his hands. The tail of the scorpion is raised ready to sting and yet Jesus looks down on it with love and compassion. The dangerous insect is enfolded within the body of Jesus and is clearly loved. Like humanity, the scorpion is held by the one in whom we live and move and have our being (Acts 1728).

It is striking that the Sahi painting is called Dalit Madonna. In the old caste system of India, the Dalits, otherwise known as Untouchables, were the lowest class and generally had a difficult and unrewarding life. Mary, who was chosen by God to give birth to Jesus, appears to have been a fairly ordinary young girl and in the Magnificat, her song of rejoicing as she accepts God’s surprising will, she delights in the fact that God has looked with favour on the lowliness of his servant by choosing the humble and casting down the mighty: He has put down the powerful from their thrones and lifted up the lowly. (Luke 146ff)

Sahi’s painting captures so much of this understanding of God our Mother and offers reassurance of the place of humanity deep within the heart of the Divine.

The poem Mothered has been set to music for SATB choir and cello by Joanna Forbes L’Estrange.

The first performance will be in St Mary’s Guildford on 29 March 2026.