Literature festivals are important for writers; and, more specifically, poetry festivals are precious for poets. They provide, of course, one of the most successful arenas for selling our books and introduce us to new audiences. They also provide opportunities for us to hear the work of other writers and discover good books that hadn’t crossed our desks before. They create space to relax, have fun and make new friends.

This past autumn, as usual, there has been a good crop of festivals for our delectation. However, in a difficult climate for the Arts, some of these are at risk, and others have had to call a halt to their activities. I attended two festivals in Italy and two in England, so will report, briefly on those, and on their chances of survival.

Villa Pia, Umbria

The first wasn’t, strictly, a festival but a Ways with Words house party at Villa Pia, a beautiful old house in Italy. My reason for going was that I had never been able to get to one of these holidays before, and it was advertised that this would definitely be the last one. Sadly, Kay Dunbar, who with her husband Steve Bristow has been the instigator, organiser and inspiration behind these residential literary holidays, is unwell and

The first wasn’t, strictly, a festival but a Ways with Words house party at Villa Pia, a beautiful old house in Italy. My reason for going was that I had never been able to get to one of these holidays before, and it was advertised that this would definitely be the last one. Sadly, Kay Dunbar, who with her husband Steve Bristow has been the instigator, organiser and inspiration behind these residential literary holidays, is unwell and  therefore unable to continue in the rôle she has so ably filled for nearly twenty years. Several of the guests had been back year after year, some staying for two weeks, rather than the one we managed.

therefore unable to continue in the rôle she has so ably filled for nearly twenty years. Several of the guests had been back year after year, some staying for two weeks, rather than the one we managed.

There was a writer in residence, Mark McCrum, who was generous with his time and encouragement; there were Italian lessons on offer, and there was a day trip to San Sepulchro. Apart from those pleasures, there was time to relax (and in my case to get some writing done), beautiful countryside to explore, a deliciously warm swimming pool and fantastic food. There was, naturally, some sadness that such a lovely annual event was coming to an end – but I was just pleased that I’d finally managed to make it at the eleventh hour.

There was a writer in residence, Mark McCrum, who was generous with his time and encouragement; there were Italian lessons on offer, and there was a day trip to San Sepulchro. Apart from those pleasures, there was time to relax (and in my case to get some writing done), beautiful countryside to explore, a deliciously warm swimming pool and fantastic food. There was, naturally, some sadness that such a lovely annual event was coming to an end – but I was just pleased that I’d finally managed to make it at the eleventh hour.

Poetry on the Lake, Orta San Giulia, Italy

The other Italian event was the wonderful Poetry on the Lake at Orta San Giulio in northern Italy, which I have attended for most of the last few years. Many of us first attended this festival when we were successful in the poetry competition that preceded it each year; and then we became addicted and continued to travel to Italy each autumn for our annual fix, even without the carrot of competition success. For several years both the last Poet Laureate (Carol Ann Duffy) and the National Poet of Wales (Gillian Clark) used to attend; but they were not there this year.

Orta is a very beautiful small town on the edge of enchanting Lake Orta, the smallest and most westerly of the northern Italian lakes. Although various members of the public, and some school parties from Milan do turn up to Poetry on the Lake , unlike most other poetry festivals, it is not primarily a public event, though we are always pleased to see the delightful Countess who comes to listen to us each year.

, unlike most other poetry festivals, it is not primarily a public event, though we are always pleased to see the delightful Countess who comes to listen to us each year.

Instead it is a convivial get-together of poets, who read to each other at a number of events over the weekend and catch up with each other’s news. The organisation is always unpredictable and exciting, and most of us have learned that, whatever the official programme suggests, one should never turn up at a reading without a batch of poems secreted in one’s pocket. One morning of the festival is spent walking on the Sacro Monte, where we stop at each of the various shrines to read poetry.

My husband and I generally drive down to Orta in our little campervan, and stay at the lakeside campsite just outside town. The walk into town and back for events is easily compensated for by the magic of waking up to sunrise over the lake, and the joy of swimming in the warm soft water each day.

So, is this a festival that is ending or continuing? Well, the rumours were that this was to be the last  one, and this was even announced in a poetry magazine over the summer. When questioned, however, the festival organiser, Gabriel Griffin, prevaricated. No, the format would not be repeated in future, and there would certainly not be another competition. But maybe, just maybe, it was just possible that something different might happen. Who knows? But even if it does not continue, many of us have hugely enjoyed returning to Orta each year and meeting up with poets who have become firm friends.

one, and this was even announced in a poetry magazine over the summer. When questioned, however, the festival organiser, Gabriel Griffin, prevaricated. No, the format would not be repeated in future, and there would certainly not be another competition. But maybe, just maybe, it was just possible that something different might happen. Who knows? But even if it does not continue, many of us have hugely enjoyed returning to Orta each year and meeting up with poets who have become firm friends.

Torbay Poetry Festival

I was back in England in time for the Torbay Poetry Festival, one of the friendliest festivals of the annual calendar. And this time, sadly, it really was the last one. Patricia and William Oxley have run the weekend festival for nineteen years, but this year they did not manage to secure Arts Council funding. I have read at the festival several times in the past, but this year I went to enjoy other people’s work. Some highlights this year were readings by Laura Potts and Imtiaz Dharker and a fascinating presentation on John Betjeman by the president of the Betjeman Society. (Yes, I know: Betjeman isn’t my favourite poet either; but it really was a most interesting and entertaining presentation and I ended up feeling friendlier to Betjeman than I had before).

I’m delighted to say that although the Torbay Poetry Festival will be no more, the poetry magazine, Acumen, also edited by Patricia Oxley, continues to flourish. Also, in terms of festivals, there are new ones each year, including the Teignmouth Poetry Festival, just along the coast, which is going from strength to strength and the more established Exeter Poetry Festival.

Poetry at Aldeburgh

Finally to Aldeburgh, which has been home to a poetry festival for years. When the plug was pulled on the old Aldeburgh Poetry Festival a few years ago, fans were so outraged that they decided to continue in an amateur, not-for-profit capacity, without financial backing. Presumably because of the lack of funding, Poetry in Aldeburgh does not, in general, attract the very biggest names; but it presents a cornucopia of equally good, if slightly less well-known poets.

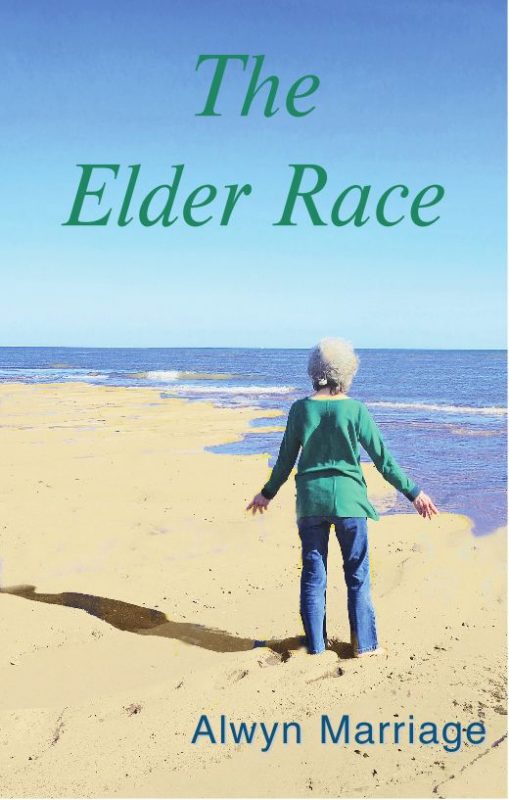

I was one of the poets reading for the launch of Coast to Coast to Coast at Aldeburgh, for which a number of us wrote poems from locations all around the coast of the British Isles. The resulting reading gave a beautiful feeling of embracing the whole of these islands. My own poem was written on Halwell Point beach, in the Salcombe Estuary in Devon.

I was one of the poets reading for the launch of Coast to Coast to Coast at Aldeburgh, for which a number of us wrote poems from locations all around the coast of the British Isles. The resulting reading gave a beautiful feeling of embracing the whole of these islands. My own poem was written on Halwell Point beach, in the Salcombe Estuary in Devon.

One of the highlights of this weekend was a dramatised reading of T S Eliot’s The Waste Land. I greatly enjoyed Martin Shaw’s story-telling session and his joint presentation the next day with the  artist and sculptor Maggie Hamlyn, who stepped in at the last minute when Gillian Beer was unwell. The Ambit cocktail party was also highly enjoyable, giving the opportunity to catch up with people who most of the time were rushing from one event to another.

artist and sculptor Maggie Hamlyn, who stepped in at the last minute when Gillian Beer was unwell. The Ambit cocktail party was also highly enjoyable, giving the opportunity to catch up with people who most of the time were rushing from one event to another.

Poetry in the Pink, Pembroke College Oxford

While most of these festivals are residential, there are others that are on-going. Among these is Poetry in the Pink at Pembroke College, Oxford, organised by Peter King, which brings good poetry to the dreaming spires on a regular basis. I was delighted to read there this last month, and have every confidence that, unlike some of the other festivals I’ve described, the future of this one is secure.

Looking ahead

This spell of festivals ended with a meeting in Glastonbury to plan, with a group of Poets for the Planet, for an event we will be presenting at the Lyra Festival in Bristol in March. By then we will be into a new year of poetry events, and our diaries, which are already filling up with next year’s poetry events, will sparkle with pleasures still to come. In the meantime, it’s good to know that even when it’s so hard to get financial support for such important events as poetry festivals, they can continue to succeed, foster new talent, encourage good writing and bang the drum for poetry in the dark days of political upheaval and tragedy.

I have always said that I adore all dance, with the single exception of tap dance; but following this Duke Ellington concert I have had to adjust my position and abandon my prejudice, because the tap dancer, Annette Walker, was nothing short of phenomenal. Interpreting several of the movements, she brought what was already a superb performance to glittering life, with dance that, while it was certainly tap dance, also often appeared to be akin to contemporary dance. One of the movements was entitled ‘David danced’, in which the chorus, jazz band and tap dance melded beautifully; but we were treated to her exquisite interpretations in several other movements as well.

I have always said that I adore all dance, with the single exception of tap dance; but following this Duke Ellington concert I have had to adjust my position and abandon my prejudice, because the tap dancer, Annette Walker, was nothing short of phenomenal. Interpreting several of the movements, she brought what was already a superb performance to glittering life, with dance that, while it was certainly tap dance, also often appeared to be akin to contemporary dance. One of the movements was entitled ‘David danced’, in which the chorus, jazz band and tap dance melded beautifully; but we were treated to her exquisite interpretations in several other movements as well. The All Stars Jazz Band underscored and held the evening together with skill and verve. Members of the band were Colin Skinner (Lead alto sax), Alan Barnes (Alto sax / clarinet) Robert Fowler (Tenor sax), Karen Sharp (baritone sax), Steve Waterman (1st trumpet), Freddie Gavita (2nd trumpet), Ian Bateman (1st trombone), Paul Sykes (2nd trombone), Rob Barron (piano), Marianne Windham (bass) and Clark Tracey (drums). I mention them by name because each was worthy of note, and raised the temperature of the evening with their solo passages.

The All Stars Jazz Band underscored and held the evening together with skill and verve. Members of the band were Colin Skinner (Lead alto sax), Alan Barnes (Alto sax / clarinet) Robert Fowler (Tenor sax), Karen Sharp (baritone sax), Steve Waterman (1st trumpet), Freddie Gavita (2nd trumpet), Ian Bateman (1st trombone), Paul Sykes (2nd trombone), Rob Barron (piano), Marianne Windham (bass) and Clark Tracey (drums). I mention them by name because each was worthy of note, and raised the temperature of the evening with their solo passages. The first dance was ‘Ripple’, an hypnotically lyrical piece choreographed by Xie Xin. In this dance, the dancers became the sea, constantly moving, swelling and subsiding, especially through the movement of their arms. Although quite a bit of the dance was scored for the whole troupe, there were several duets, in which a hand would reach out towards the partner’s hand, only to be retracted before they could touch.

The first dance was ‘Ripple’, an hypnotically lyrical piece choreographed by Xie Xin. In this dance, the dancers became the sea, constantly moving, swelling and subsiding, especially through the movement of their arms. Although quite a bit of the dance was scored for the whole troupe, there were several duets, in which a hand would reach out towards the partner’s hand, only to be retracted before they could touch.

I was never particularly keen on brass instruments until I met the man who was destined to be my husband. To my delight, he actually serenaded me on his trumpet with Caro mio bien, … and my life was changed for ever.

I was never particularly keen on brass instruments until I met the man who was destined to be my husband. To my delight, he actually serenaded me on his trumpet with Caro mio bien, … and my life was changed for ever. the band’s cup for the player who had made the most improvement; but I’m sure that was only because I had started from such a low base!

the band’s cup for the player who had made the most improvement; but I’m sure that was only because I had started from such a low base! for us to play carols at pubs, open air gatherings and the local nativity play; and in summer, we expended all the breath we didn’t know we had, by processing

for us to play carols at pubs, open air gatherings and the local nativity play; and in summer, we expended all the breath we didn’t know we had, by processing  down Fore Street from top to bottom playing the Floral Dance (ad infinitum), while the rest of the town danced along in their festive clothes behind us. This is generally great fun, though the year we had to do this in pouring rain took slightly more determination. More

down Fore Street from top to bottom playing the Floral Dance (ad infinitum), while the rest of the town danced along in their festive clothes behind us. This is generally great fun, though the year we had to do this in pouring rain took slightly more determination. More  restfully, we played each summer for an open-air service at Hope Cove, put on by the Methodist church; in November we normally do our civic duty by playing for the Remembrance Day Parade; and we perform in the bandstand in Kingsbridge on various occasions.

restfully, we played each summer for an open-air service at Hope Cove, put on by the Methodist church; in November we normally do our civic duty by playing for the Remembrance Day Parade; and we perform in the bandstand in Kingsbridge on various occasions.

residents; and some of them have been in the band for more decades than one could imagine (over 70 years in one case!). The age range has therefore been between 12 and 90 plus.

residents; and some of them have been in the band for more decades than one could imagine (over 70 years in one case!). The age range has therefore been between 12 and 90 plus.

and a fascinating project entitled ‘New York Beautification Project’, in which she painted tiny, perfectly-executed graffiti cameos on items all around the streets of New York, intentionally confining herself to sites on which she did not have permission to paint her work. Here are some examples of the paintings with which she ‘beautified’ some items that are normally considered ugly.

and a fascinating project entitled ‘New York Beautification Project’, in which she painted tiny, perfectly-executed graffiti cameos on items all around the streets of New York, intentionally confining herself to sites on which she did not have permission to paint her work. Here are some examples of the paintings with which she ‘beautified’ some items that are normally considered ugly.

The first wasn’t, strictly, a festival but a Ways with Words house party at Villa Pia, a beautiful old house in Italy. My reason for going was that I had never been able to get to one of these holidays before, and it was advertised that this would definitely be the last one. Sadly, Kay Dunbar, who with her husband Steve Bristow has been the instigator, organiser and inspiration behind these residential literary holidays, is unwell and

The first wasn’t, strictly, a festival but a Ways with Words house party at Villa Pia, a beautiful old house in Italy. My reason for going was that I had never been able to get to one of these holidays before, and it was advertised that this would definitely be the last one. Sadly, Kay Dunbar, who with her husband Steve Bristow has been the instigator, organiser and inspiration behind these residential literary holidays, is unwell and  therefore unable to continue in the rôle she has so ably filled for nearly twenty years. Several of the guests had been back year after year, some staying for two weeks, rather than the one we managed.

therefore unable to continue in the rôle she has so ably filled for nearly twenty years. Several of the guests had been back year after year, some staying for two weeks, rather than the one we managed.

There was a writer in residence, Mark McCrum, who was generous with his time and encouragement; there were Italian lessons on offer, and there was a day trip to San Sepulchro. Apart from those pleasures, there was time to relax (and in my case to get some writing done), beautiful countryside to explore, a deliciously warm swimming pool and fantastic food. There was, naturally, some sadness that such a lovely annual event was coming to an end – but I was just pleased that I’d finally managed to make it at the eleventh hour.

There was a writer in residence, Mark McCrum, who was generous with his time and encouragement; there were Italian lessons on offer, and there was a day trip to San Sepulchro. Apart from those pleasures, there was time to relax (and in my case to get some writing done), beautiful countryside to explore, a deliciously warm swimming pool and fantastic food. There was, naturally, some sadness that such a lovely annual event was coming to an end – but I was just pleased that I’d finally managed to make it at the eleventh hour.

, unlike most other poetry festivals, it is not primarily a public event, though we are always pleased to see the delightful Countess who comes to listen to us each year.

, unlike most other poetry festivals, it is not primarily a public event, though we are always pleased to see the delightful Countess who comes to listen to us each year.

one, and this was even announced in a poetry magazine over the summer. When questioned, however, the festival organiser, Gabriel Griffin, prevaricated. No, the format would not be repeated in future, and there would certainly not be another competition. But maybe, just maybe, it was just possible that something different might happen. Who knows? But even if it does not continue, many of us have hugely enjoyed returning to Orta each year and meeting up with poets who have become firm friends.

one, and this was even announced in a poetry magazine over the summer. When questioned, however, the festival organiser, Gabriel Griffin, prevaricated. No, the format would not be repeated in future, and there would certainly not be another competition. But maybe, just maybe, it was just possible that something different might happen. Who knows? But even if it does not continue, many of us have hugely enjoyed returning to Orta each year and meeting up with poets who have become firm friends.

I was one of the poets reading for the launch of Coast to Coast to Coast at Aldeburgh, for which a number of us wrote poems from locations all around the coast of the British Isles. The resulting reading gave a beautiful feeling of embracing the whole of these islands. My own poem was written on

I was one of the poets reading for the launch of Coast to Coast to Coast at Aldeburgh, for which a number of us wrote poems from locations all around the coast of the British Isles. The resulting reading gave a beautiful feeling of embracing the whole of these islands. My own poem was written on  artist and sculptor Maggie Hamlyn, who stepped in at the last minute when Gillian Beer was unwell. The Ambit cocktail party was also highly enjoyable, giving the opportunity to catch up with people who most of the time were rushing from one event to another.

artist and sculptor Maggie Hamlyn, who stepped in at the last minute when Gillian Beer was unwell. The Ambit cocktail party was also highly enjoyable, giving the opportunity to catch up with people who most of the time were rushing from one event to another.

Nowhere else can one find so many frescoes by Giotto and Cimabue and I could (and do when possible) spend many hours contemplating the vision of these artists. This does not mean, however, that I am entirely uncritical of the treatment of all the subjects portrayed.

Nowhere else can one find so many frescoes by Giotto and Cimabue and I could (and do when possible) spend many hours contemplating the vision of these artists. This does not mean, however, that I am entirely uncritical of the treatment of all the subjects portrayed. initially living a life of pleasure and ease, Francis had an epiphany that caused him to give up all worldly wealth and privilege to become a humble friar. It may well be that he appeared at a point in history when his message was needed, and he simply ignited a fuse that was ready to burst into life; but he was also clearly a charismatic character, who quickly attracted huge numbers of followers and gradually formed what became known as the Franciscan Order. As is often the case with these special personalities, stories accrued around the basic facts of his life, and a number of miracles were ascribed to him both during his lifetime and afterwards.

initially living a life of pleasure and ease, Francis had an epiphany that caused him to give up all worldly wealth and privilege to become a humble friar. It may well be that he appeared at a point in history when his message was needed, and he simply ignited a fuse that was ready to burst into life; but he was also clearly a charismatic character, who quickly attracted huge numbers of followers and gradually formed what became known as the Franciscan Order. As is often the case with these special personalities, stories accrued around the basic facts of his life, and a number of miracles were ascribed to him both during his lifetime and afterwards.

And, as I have mentioned, it is nothing short of a miracle that a young teenager can motivate so many people all around the world, to rise up and demand action on climate change, and can also be invited to meet some of the movers and shakers of the world and speak with authority at international events.

And, as I have mentioned, it is nothing short of a miracle that a young teenager can motivate so many people all around the world, to rise up and demand action on climate change, and can also be invited to meet some of the movers and shakers of the world and speak with authority at international events.

but as we had been watching the film of Oscar Wilde, with our mobile ‘phones turned off, we hadn’t received the message asking us to head for dry land. We drove out and found a quiet spot beside the road on higher ground, where we enjoyed a peaceful night’s sleep. The next day we booked into a b&b for the rest of the week, which was just as well as the campsite had still not re-opened by the time we left. By then, not only was the campsite underwater, but most of the surrounding fields and woodland.

but as we had been watching the film of Oscar Wilde, with our mobile ‘phones turned off, we hadn’t received the message asking us to head for dry land. We drove out and found a quiet spot beside the road on higher ground, where we enjoyed a peaceful night’s sleep. The next day we booked into a b&b for the rest of the week, which was just as well as the campsite had still not re-opened by the time we left. By then, not only was the campsite underwater, but most of the surrounding fields and woodland. ‘There is no Planet B’. The well-researched information in his talk could not fail to shock, but he also found a way to offer at least some hope that all is not yet lost – as long as we all take the threat extremely seriously, and act now to save the planet.

‘There is no Planet B’. The well-researched information in his talk could not fail to shock, but he also found a way to offer at least some hope that all is not yet lost – as long as we all take the threat extremely seriously, and act now to save the planet. Peter Sanford appeared in the main theatre to give a talk entitled ‘Angelology’. Peter is a gifted lecturer and held us spellbound as he explored the history and mythology of belief in angels. He quoted the surprising statistic that one in ten Britons claims to have experienced the presence of an angel. It would appear that many of these people believe in ‘guardian angels’, rather than in the more general, and more interesting idea of angels being messengers from God.

Peter Sanford appeared in the main theatre to give a talk entitled ‘Angelology’. Peter is a gifted lecturer and held us spellbound as he explored the history and mythology of belief in angels. He quoted the surprising statistic that one in ten Britons claims to have experienced the presence of an angel. It would appear that many of these people believe in ‘guardian angels’, rather than in the more general, and more interesting idea of angels being messengers from God. Marcus du Sautoy Melissa Benn

Marcus du Sautoy Melissa Benn

Viola’s world and receives a glimpse of his spiritual awareness. The cleansing of one’s normal attention also made the Michelangelo drawings that much more striking, as one became conscious of the way in which the artist conveys so much of the important essence of the figures with so few strokes of the brush or pen, whether it be a depiction of Christ’s crucifixion, the risen Christ (pictured right) or the tenderness of a nativity scene.

Viola’s world and receives a glimpse of his spiritual awareness. The cleansing of one’s normal attention also made the Michelangelo drawings that much more striking, as one became conscious of the way in which the artist conveys so much of the important essence of the figures with so few strokes of the brush or pen, whether it be a depiction of Christ’s crucifixion, the risen Christ (pictured right) or the tenderness of a nativity scene.