In 2007, Anne Born, the Managing Editor of Oversteps Books, invited me to submit a manuscript for publication, which she promptly  accepted. She wanted to have the book published in time for Ways with Words at Dartington that July, so moved the book through the production process quite quickly, and ‘Touching Earth’ came out in good time for the festival. The collection included various sections including science and ecology, and the experience of being a woman. Later, Anne commissioned me to put together a collection of my winter and Christmas poems, but this book, ‘Festo’ was not published until after her death.

accepted. She wanted to have the book published in time for Ways with Words at Dartington that July, so moved the book through the production process quite quickly, and ‘Touching Earth’ came out in good time for the festival. The collection included various sections including science and ecology, and the experience of being a woman. Later, Anne commissioned me to put together a collection of my winter and Christmas poems, but this book, ‘Festo’ was not published until after her death.

The following year, Anne became ill and I went to visit her. ‘Anything I can do to help, Anne’ I enquired, thinking she might like me to take some parcels to the post office.

‘Yes’, she replied. ‘I want you to take over Oversteps’.

I must admit that running a publishing house was not something on my wish-list, and I wriggled for over an hour before I accepted her ‘kind offer’. I was already busy with my own writing, as well as a full programme of guest lecturing and readings, and I was also working as an environmental consultant; but Anne was nothing if not determined and persistent, so before I left her house that afternoon, I had agreed to become Managing Editor. There then followed a steep learning curve.

Ten years on, I am pleased that I have had the opportunity to publish books by so many good poets. The logo on the left is the original one, which shows the back steps up to Anne’s lovely house in South Devon. To balance this , I designed a new, more modern one, and I have used both ever since (see right).

Ten years on, I am pleased that I have had the opportunity to publish books by so many good poets. The logo on the left is the original one, which shows the back steps up to Anne’s lovely house in South Devon. To balance this , I designed a new, more modern one, and I have used both ever since (see right).

My first ‘discovery’ was made that spring, when I looked up a poem of mine in the Irish magazine The SHOp while visiting the Scottish Poetry Library. There I found work by a poet called Miriam Darlington, to which I responded enthusiastically.

I traced Miriam to Devon (where Oversteps is based), and that July, her book, ‘Windfall’ was published, once again in time for a reading at Ways with Words. We were in business. Miriam has since then undertaken a PhD in Creative Writing, and is now a regular contributor to the Sunday Times with her nature writing.

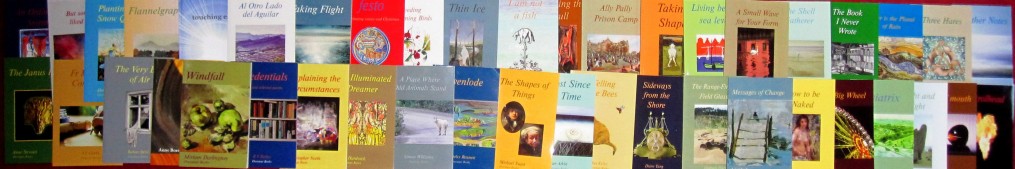

In the last ten years, I have published something in the region of 90 books, and Oversteps Books has taken up a great deal of my waking hours, though I’m pleased to report that it has not stopped my own writing. I will write in my next blog about the many opportunities poets now have for being published; but for this one, I’ll share some information about getting published by Oversteps.

To start with I published twelve books a year; as the work grew and Oversteps became better known, I found it necessary to reduce this to ten books per year; and I am now endeavouring to limit the production to eight books per year. Our books are well-reviewed and Oversteps poets give readings at many of the major festivals and poetry venues.

How does one go about having a book published by Oversteps? Full details are on the Oversteps website (www.overstepsbooks.com), but here are a few markers.

First, we publish only poetry, and accept submissions only from poets who have had a decent number of poems published in respected poetry journals or have won major competitions. This is just to keep the submissions to a manageable number; but even so, I sometimes receive as many as 300 submissions in a year.

From those submissions, I select between two dozen and thirty of the best poets, who are then invited to submit whole collections; and these are put before the Editorial Board at one of the two meetings we hold each year. No one knows who the members of this committee are — in order to avoid any arm-twisting; and the members of the board have no idea whose collections they are considering, as they are presented with the submissions ‘blind’. They have several weeks to work on the manuscripts before the meetings, and we then meet for several hours to thrash out which few books we can take forward to publication. Because of the ‘blind’ system, it really is the case that the poetry is judged on its own merits, and I happen to know that some quite well-known poets have not managed to squeeze through on occasions. I often wish I could take on more of the poets, as most of the collections that get this far in the process are certainly worthy of publication; but I simply cannot take on more books than I do at present.

I then contact the successful poets with the good news, and prepare memoranda of agreement for them to sign. At the same time, I have the unpleasant task of turning down those who did not make it. I hate having to do this, and am grateful that most poets respond graciously to this bad news; but there have been a handful whose responses have been less than pleasant. A few of the poets who were very close to being accepted have been offered the possibility of re-submiting later, and some of these have been successful.

I use desk-top publishing software to work on the manuscripts, and negotiate closely with the poets all through the process. I am a very fussy editor, and I’m glad to say that we have managed to avoid any typos or other mistakes in the finished books, largely because the manuscripts go back and forth between me and the poet many many times before I’m satisfied.

The poets generally like to provide their own artwork for their covers, and one of the tasks I most enjoy is designing those covers. The books are produced to extremely high standards in terms of both editing and design, and we receive many very favourable reviews.

With the first book (Windfall) I developed a house style that would allow a huge range of variations, while still remaining recognisably Oversteps.

Once I’ve checked the final proof and ordered the books from our extremely helpful printer, I can start on the post-publication work, which includes adding the new book to our website and sending out a newsletter about it. I register the new book with Nielsens, send copies to the six deposit libraries and the Poetry Library, inform organisations such as the Poetry Society, decide which magazines I should send review copies to and send those off in the hope that we might get reviews, pay the printer and sell as many copies as I can to recoup some of the costs. Poets are expected to help with the marketing and to arrange some readings, but I also organise some high-profile events at which they can read their work.

As you will have gathered from my description of the submissions process, the chances of being accepted by Oversteps are not high. But for the fortunate few who do manage to squeeze through the net, they will not only have a published book to be proud of, but will also be part of a successful and supportive group of poets.

When I took over as Managing Editor, I managed to secure a couple of grants from the Arts Council, which allowed me to purchase some necessary equipment and software. I have never applied for funding since then, as I was aware that other endeavours that were dependent on external funding often found that they could not survive when that funding was withdrawn. I therefore tried to make Oversteps self-financing. This was, of course, only possible as long as it was not necessary to provide salaries. I’m pleased to say that we have managed to survive on this basis through the difficult economic conditions of the last ten years. But I have to admit that it is getting more difficult, and there are questions as to how much longer we can stay afloat. There is a constant stream of book orders, most of which come through our website, and our wonderful poets help by giving readings and selling books themselves; and a small handful of our poets have returned again and again for reprints, pushing their sales figures up into the thousands. I am deeply grateful to them.

I am also grateful for the unexpected skills I have had to acquire. It has sometimes been challenging having to struggle with new technology, but most of it has been fun. I have also made a huge number of new friends, many of whom have become important parts of my life. I am always surprised when I first hear a new poet reading from their Oversteps book at a public event. Having been close to the work for many months, it suddenly comes alive in a new and exciting way. We have been fortunate to be given reading gigs at festivals and other events all over the country; but our special thanks must go to Ways with Words in Dartington, Devon, who give us a whole day every year — the festival’s Oversteps Day — to present the work of Oversteps poets. This year the Oversteps Day will be on July 14th, and I hope to see many of you there. Before that, there is a group reading at the Poetry Café in London, on Thursday 7th June. And there are many other opportunities to hear our poets reading. I include some of the forthcoming readings, as well as news about competition successes, in the Oversteps newsletter <overstepsbooks.wordpress.com>.

After ten successful years, questions are bound to arise about the future. The more Oversteps grows and prospers, and the number of poets continues to multiply, the harder it is for one person to manage the whole business; but this blog is just to celebrate the first ten years. The future will unfold in its own sweet time. In the meantime, I’d like to send warm thanks to all who have made Oversteps so successful: the poets (particularly the poets!), those who have bought books from us, those who have given us readings and other gigs, those who have responded to my newsletters — and to my long-suffering husband.

Most of you probably know that I am a huge fan of Ways with Words, the literature and ideas festival that’s held at Dartington Hall in Devon every July. It was started in 1991 by Kay Dunbar and Steve Bristow, who ran it every year until they took a back seat this year, handing it on to their fantastic staff, Leah, Jane and Phil, to keep up the good work

Most of you probably know that I am a huge fan of Ways with Words, the literature and ideas festival that’s held at Dartington Hall in Devon every July. It was started in 1991 by Kay Dunbar and Steve Bristow, who ran it every year until they took a back seat this year, handing it on to their fantastic staff, Leah, Jane and Phil, to keep up the good work

Mark Oakley is Canon Chancellor at St Paul’s Cathedral, though he will be moving at the end of next month, to take up the post of Dean of St John’s College, Cambridge. He is also a poetry-lover, with a keen ear and discriminating mind. In his recent book, ‘The Splash of Words: Believing in Poetry’, he has selected and presented twenty-nine poems, from all ages and in all forms, in each case then going on to a wide-ranging discussion of the work, his response to it, and his personal and faith journey. It makes riveting reading, and because practically all the poems are ones I have loved for years, reading it was like meeting up with old friends and forming an even deeper acquaintance with them.

Mark Oakley is Canon Chancellor at St Paul’s Cathedral, though he will be moving at the end of next month, to take up the post of Dean of St John’s College, Cambridge. He is also a poetry-lover, with a keen ear and discriminating mind. In his recent book, ‘The Splash of Words: Believing in Poetry’, he has selected and presented twenty-nine poems, from all ages and in all forms, in each case then going on to a wide-ranging discussion of the work, his response to it, and his personal and faith journey. It makes riveting reading, and because practically all the poems are ones I have loved for years, reading it was like meeting up with old friends and forming an even deeper acquaintance with them.

accepted. She wanted to have the book published in time for Ways with Words at Dartington that July, so moved the book through the production process quite quickly, and ‘Touching Earth’ came out in good time for the festival. The collection included various sections including science and ecology, and the experience of being a woman. Later, Anne commissioned me to put together a collection of my winter and Christmas poems, but this book, ‘Festo’ was not published until after her death.

accepted. She wanted to have the book published in time for Ways with Words at Dartington that July, so moved the book through the production process quite quickly, and ‘Touching Earth’ came out in good time for the festival. The collection included various sections including science and ecology, and the experience of being a woman. Later, Anne commissioned me to put together a collection of my winter and Christmas poems, but this book, ‘Festo’ was not published until after her death.

Ten years on, I am pleased that I have had the opportunity to publish books by so many good poets. The logo on the left is the original one, which shows the back steps up to Anne’s lovely house in South Devon. To balance this , I designed a new, more modern one, and I have used both ever since (see right).

Ten years on, I am pleased that I have had the opportunity to publish books by so many good poets. The logo on the left is the original one, which shows the back steps up to Anne’s lovely house in South Devon. To balance this , I designed a new, more modern one, and I have used both ever since (see right).

seesaw. Balance was obviously key to this piece, and already the dancers appeared to have shed all their human weight, enabling them to appear to be almost flying. They rocked, see-sawed, slid, tipped and balanced. While the dance was fun and absorbing, the sound track for this piece was challenging and, as well as more conventional instruments, included rap and whispers. It was only when I read the programme when I got home that I discovered that one of the singing voices in this track was our friend Joanna Forbes L’Estrange.

seesaw. Balance was obviously key to this piece, and already the dancers appeared to have shed all their human weight, enabling them to appear to be almost flying. They rocked, see-sawed, slid, tipped and balanced. While the dance was fun and absorbing, the sound track for this piece was challenging and, as well as more conventional instruments, included rap and whispers. It was only when I read the programme when I got home that I discovered that one of the singing voices in this track was our friend Joanna Forbes L’Estrange. Trousers came off for the next piece, ‘Human Animal’, in which the dancers, clad in floral shirts and black underpants, started by walking round the stage pawing at the ground like horses, then performing other movements reminiscent of equestrian dressage.

Trousers came off for the next piece, ‘Human Animal’, in which the dancers, clad in floral shirts and black underpants, started by walking round the stage pawing at the ground like horses, then performing other movements reminiscent of equestrian dressage.

ut.

ut.

Deaf, blind, angry, poor and religious, Jack had difficulty forming relationships, but became convinced that God intended him to marry. The prospects for future marital happiness were not great, but then, in 1967, he received a letter out of the blue from Ruth Peaty, wanting to get to know him because ‘I think you are an interesting personality’. A strange correspondence began which led, the following summer, to a meeting and, on 26th October 1967, to Jack and Ruth’s marriage. During the following year Jack wrote more poetry than he had ever done before.

Deaf, blind, angry, poor and religious, Jack had difficulty forming relationships, but became convinced that God intended him to marry. The prospects for future marital happiness were not great, but then, in 1967, he received a letter out of the blue from Ruth Peaty, wanting to get to know him because ‘I think you are an interesting personality’. A strange correspondence began which led, the following summer, to a meeting and, on 26th October 1967, to Jack and Ruth’s marriage. During the following year Jack wrote more poetry than he had ever done before. How did one communicate with this great man? He could, of course, speak, though one had to bend towards him and listen carefully to catch his words. Then came the practice of speaking on his hand, tracing capital letters and spelling out each word until he grasped what one was trying to say. This unusual way of communication slowed conversation down to an extent, but it was intensely moving. I remember my first experience of communicating with Jack in this way, when I realised that here was an entirely different method of human interaction. It reminded me of the first time I encountered geysers and bubbling mud in New Zealand, when it dawned on me that I’d never see the ground beneath my feet in quite the same way again.

How did one communicate with this great man? He could, of course, speak, though one had to bend towards him and listen carefully to catch his words. Then came the practice of speaking on his hand, tracing capital letters and spelling out each word until he grasped what one was trying to say. This unusual way of communication slowed conversation down to an extent, but it was intensely moving. I remember my first experience of communicating with Jack in this way, when I realised that here was an entirely different method of human interaction. It reminded me of the first time I encountered geysers and bubbling mud in New Zealand, when it dawned on me that I’d never see the ground beneath my feet in quite the same way again.

Bed, which was written soon afterwards, but not published until 1986.

Bed, which was written soon afterwards, but not published until 1986.

far too little. The other part of my delight was because I recognised that with such a lovely group of poets we were bound to have fun. The other poets were Maggie Butt, Katherine Gallagher, Jeremy Page, Peter Phillips and Anne Stewart. I had published Maggie and Anne as Oversteps poets, and was well aware of the fine reputation of the others.

far too little. The other part of my delight was because I recognised that with such a lovely group of poets we were bound to have fun. The other poets were Maggie Butt, Katherine Gallagher, Jeremy Page, Peter Phillips and Anne Stewart. I had published Maggie and Anne as Oversteps poets, and was well aware of the fine reputation of the others.

book was called simply ‘Six British Poets’. Our poems were translated by Ioana Ieronim, and published by Integral Press, Bucharest. I’m pictured here with Ioana, the translator.

book was called simply ‘Six British Poets’. Our poems were translated by Ioana Ieronim, and published by Integral Press, Bucharest. I’m pictured here with Ioana, the translator. mous amount of fun, and were looked after royally by our hosts. We had a memorable dinner at ‘Lacrimi si Sfinti’, the restaurant belonging to Mircea Dinescu. Mircea is one of the best-known Romanian poets, was very much involved in the Revolution against Ceausescu in 1989, and now owns a farm out in the country where he grows all the food

mous amount of fun, and were looked after royally by our hosts. We had a memorable dinner at ‘Lacrimi si Sfinti’, the restaurant belonging to Mircea Dinescu. Mircea is one of the best-known Romanian poets, was very much involved in the Revolution against Ceausescu in 1989, and now owns a farm out in the country where he grows all the food  and wine for his fantastic restaurant in Bucharest. Here he is pictured with his wife, Maria; and in the other picture you can see the band that entertained us as we ate.

and wine for his fantastic restaurant in Bucharest. Here he is pictured with his wife, Maria; and in the other picture you can see the band that entertained us as we ate.

wonderful welcome in Perth. Glen was the joint author with my predecessor, Anne Born, of ‘Singing Granites: Poems of Devon and Gondwanaland‘, which was the second book I published after I took over as Managing Editor of Oversteps Books

wonderful welcome in Perth. Glen was the joint author with my predecessor, Anne Born, of ‘Singing Granites: Poems of Devon and Gondwanaland‘, which was the second book I published after I took over as Managing Editor of Oversteps Books